“People still think there is a social stigma with head lice,” said Dr. Patricia Quinlisk, the medical director of the Iowa Department of Public Health.

In fact, many parents immediately become defensive when they learn of an infestation, and some school staffers may overreact, too.

“But lice affect every socio-economic class, every school in the state,” Quinlisk said.

“It’s common. People get this,” she added. And since lice do not carry disease in this part of the country, they are mainly a nuisance.

Joan Jutting knows all about the subject. The head nurse in the Davenport School District said lice were active in the schools when her children were young 30 years ago.

“My own kids went through this experience. It has not changed,” she said.

What has changed is school districts’ policies in reaction to an infestation. Not so long ago, students were immediately banned from the classroom until they could prove they were lice-free.

But updated research shows that when children are made to stay home from school, they are prevented from learning. And the more days they miss, the less they are able, or motivated, to learn.

Now, districts basically require that each head lice case be treated at the school nurse’s discretion and that students may stay in school as long as treatment has begun.

Lice should not keep kids out of school, Quinlisk agreed, adding that most infestations are thought to originate outside school settings.

Students with head lice who become disruptive in class may be sent home at a nurse’s discretion, Jutting said. But the usual approach is to inform the parents and provide them with the guidelines for a 14-day treatment program, which normally involves using products available at area drug stores and pharmacies.

Lice are everywhere

Head lice are found worldwide and have been present for centuries. In the United States, infestations are most common among preschool children attending child care centers and elementary schoolchildren, or the families of those children, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC.

An estimated 6 million-12 million infestations occur each year in the United States among children 3-11 years old, the CDC reports.

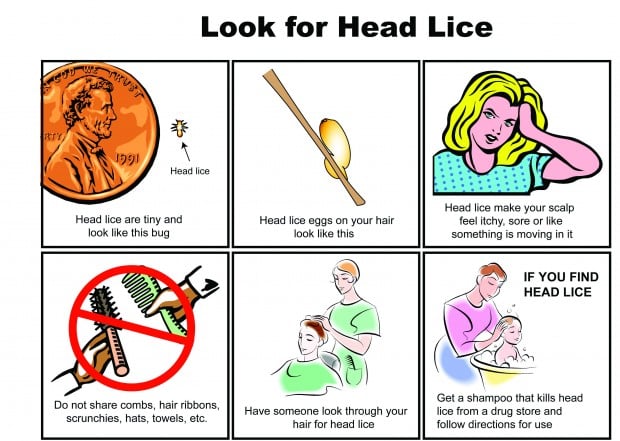

The biggest problem is with the nits, or lice eggs, tiny white specks that are commonly found closest to the scalp. They can hatch and cause the infestation to last longer.

The latest evidence-based research — offered by the Scott County Health Department to all of the county’s public and private school systems — explains the lice life cycle and how best to remove them, said Roma Taylor, the department’s clinics coordinator.

No sharing, watchfulness recommended

Lice, which are grayish-brown in color, crawl; they do not jump or fly, Jutting explained. They also do not live for more than two days, unless they are on a human host from which they can get a supply of blood.

It is suggested that parents watch the scalps of their children for lice and to guard against situations in which they might spread. Nits usually appear first near the ears and at the base of the scalp.

“One louse can lay multiple eggs,” Jutting said.

Other preventative actions that may be taken include telling your children there should be no sharing of combs, hats, headbands, scarves, and bringing a child’s own pillow and blanket to sleepovers.